Sitings: Luis Antonio Santos' "The Flowers are Blooming Again, But They Have No Scent"

In which I pick up my series for this newsletter, where I send out some of the writing I do that never make it past the sites that the exhibitions they were written for inhabit.

In The Flowers are Blooming Again But They Have No Scent, Luis Antonio Santos furthers his interrogations of loss, entropy, and memory through a culmination of his most recent explorations, particularly through the means of production itself. Using processes outside of traditional painting, Santos considers these intangible notions and expresses them through tangible objects and the way things are made.

Although used as a means of reproduction, screen printing is a very involved process. Many mistake it as a shortcut for mark-making, as the option of reproduction is there, but how one gets there is a feat in itself. The ink or paint leaving an impression may take a fraction of the time it would have taken to paint the same image, but the work that goes into making this swiftness possible is often an invisible labour.

Galvanised iron sheets — an oft-used motif and medium in Santos’ work — exist in this exhibition as subject, object, and material, as oil paintings, photographs, silkscreen paintings, the material itself. First appearing in Structures1 , G.I. sheets continue to pervade the artist’s practice.

“Untitled (Structures)”

2023

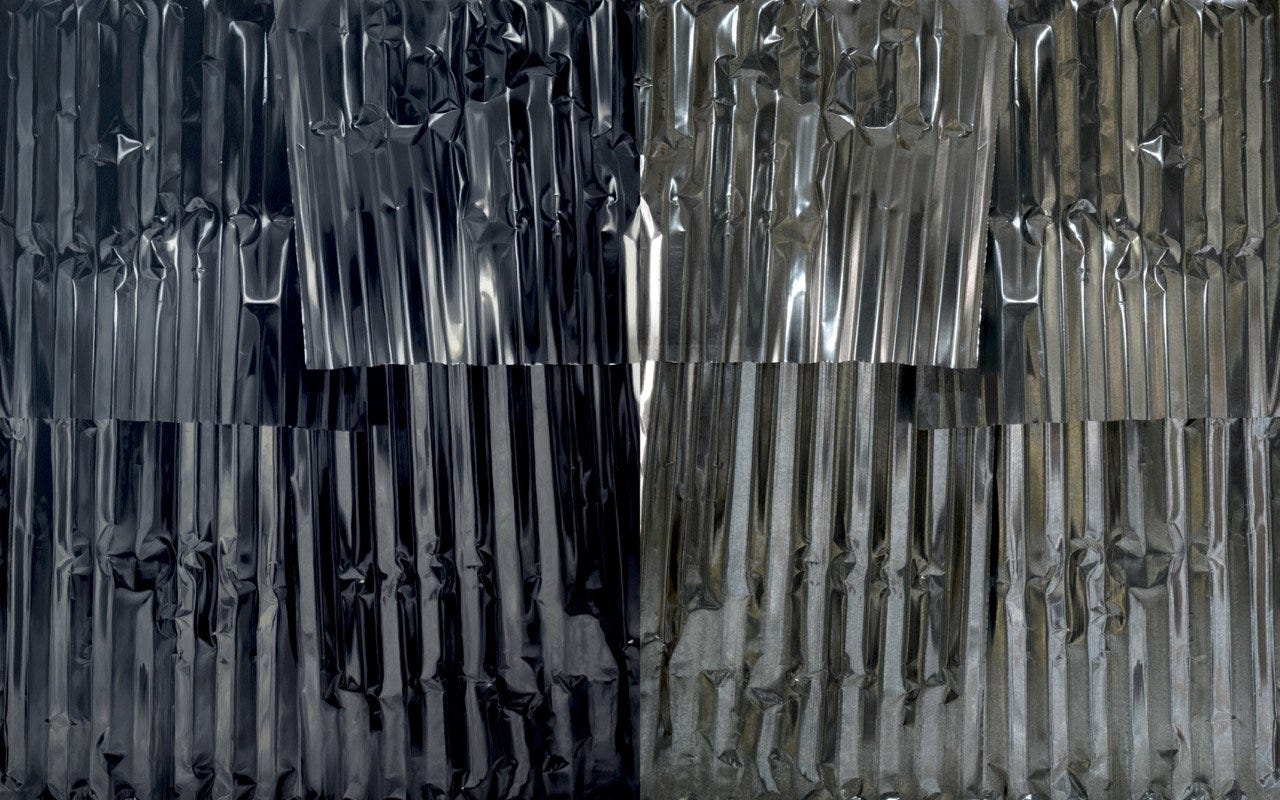

In Santos’ “Untitled (Structures)”, a diptych formation of a distorted galvanised iron sheet, set beside its mirror image: an oil painting, rendered hyper realistically, as is Santos’ way, and offering the uncanniness of the confrontation of the real with its close to perfect facsimile. Beside each other, their boundaries are dislocated and unclear. He attempts to copy the material as closely as possible: every groove, shadow, and reflection of light that he can see, but the copy is not perfect and it never will be, because it cannot be done. The light shifts, and it shifts, too. Environmental impressions change the painting from how it left his studio, and it is no longer the same.

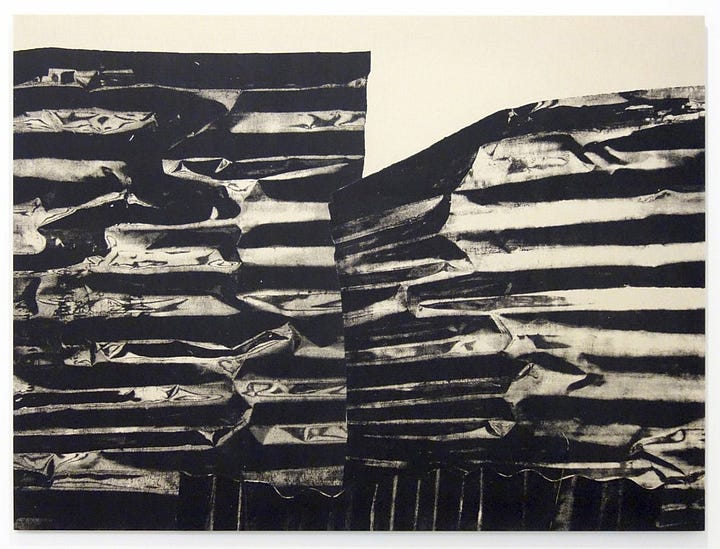

“Untitled (Structures) IV” and “Untitled (Structures) III”

2023

Both processes — painting and printing — are laborious to begin with. Santos begins with manually deforming the sheets, which requires physical exertion and a deliberate hand, and then he mounts the sheets and photographs them in set configurations, before he even approaches the initial steps of the final chosen medium.

For a different series with the same name, Santos creates paintings using imagery from the first iterations of Structures. Applied to linen, these different mangled sheets create a collage: an illusion of structures that define and separate two spaces. Boundaries are drawn immediately, though it is unclear what spaces are being delineated.

Santos’ usage of silkscreens is unorthodox, in that the resulting images are one-offs: singular configurations that are pointedly not repeated, a seeming antithesis to the process’ original purpose of making duplications.

Using “common objects” as a metaphor for both the personal and the universal, Santos ascribes to these objects notions of isolation, displacement, and dislocation, projecting on these inanimate objects deep and complex feelings and ideas that they are undoubtedly imbued in.

Playing with notions of invisibility, Santos brings these objects of ubiquity to the fore. Many of the imagery and mediums he uses escapes our gaze, because in their familiarity, we wholly consume them. Because they are often ignored or simply unseen, there is a loss of information, a fading image. Ghostly impressions that make up the world we know, yet they never quite come to mind when we are trying to paint a picture from our thoughts.

In “post—site No. 8”, a continuation of his explorations of the reversal of impressions, painting absence and negative space instead. Like in his previous exhibitions, (sun in an empty room) and Threshold, the imagery is highlighted in reverse and printed in white UV ink on clear plexiglass. Here, Santos uses images taken in the nighttime around his home, freezing moments in stark flash. Light captures the moment, and in that instance, the moment has passed. We bear witness to loss; we are looking at the past.

The images, although upended and in a different state, we recognise despite the lingering uncanniness. Our faculties reconstruct the gaps accordingly. The image shifts depending on who looks at it, when, and from where. It will never be viewed in the same way. Although we inhabit the same spaces, and looking at one image, we will never be looking at the same thing.

Each person, even when confronted by the same thing, will hold it in their psyche a little differently. How we experience an object will vary accordingly. History informs the present and it is inescapable. Susan Sontag writes in On Photography about this very notion: “As photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure.”2

“Void (I)”

2023

Santos’ body of work is a transgression of set boundaries of medium, compartmentalisations and categories. Perhaps it could simply be taken as a semantic exercise, but here, particularly in “Untitled (Structures)”, Santos turns over the idea of paintings as two-dimensional representations of an object and insists on them being three-dimensional objects as well. Beside each other, there is no doubt that they both represent a painting as object and an object as painting.

Santos continues to study the relationship between a photograph and loss. The very instant a particular moment is captured, in light and celluloid, it is a moment that is lost. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes writes: “What the Photograph reproduces to infinity has occurred only once: the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially.”3 A photograph is evidence of something transpiring, yes, but it is also proof of loss:

“In the Photograph, the event is never transcended for the sake of something else: the Photograph always leads the corpus I need back to the body I see; it is the absolute Particular, the sovereign Contingency, matte and somehow stupid, the This (this photograph, and not Photography), in short, what Lacan calls the Tuche, the Occasion, the Encounter, the Real, in its indefatigable expression.”

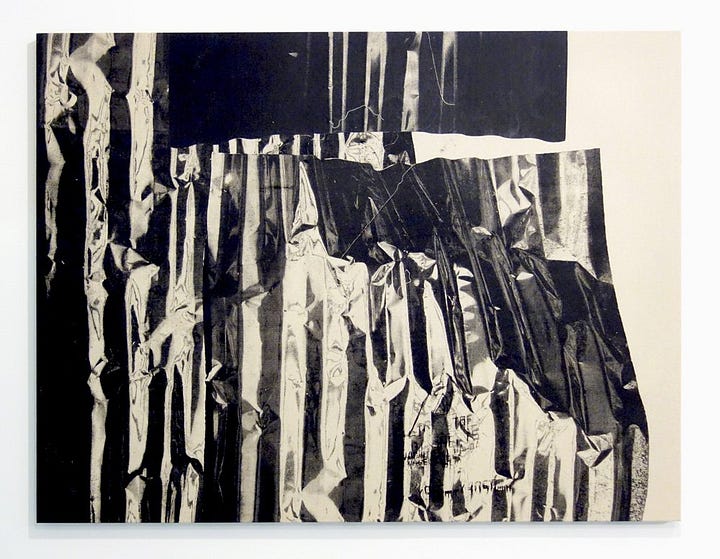

“Void (II)”

2023

Entropy is inevitable, and we — our memories, our identities — are shaped by it. In “Void”, a series of oil paintings of fabric and plastic bags draped over paintings being prepared to be framed, Santos ruminates on both loss and the division of space. The behaviour of a singular colour — a neutral material — is dependent on its surroundings: the rigid structure it’s placed upon, how it has been illuminated. Instead of asking what the light has done to the subject, the light becomes the subject, the material (in this case, the colour black) foregrounds what is often thought of as what makes things visible.

In Camera Lucida, Barthes continues: “In order to designate reality, Buddhism says sunya, the void; but better still: tathata, as Alan Watts has it, the fact of being this, of being thus, of being so; tat means that in Sanskrit and suggests the gesture of the child pointing his finger at something and saying: that, there it is, lo! but says nothing else; a photograph cannot be transformed (spoken) philosophically, it is wholly ballasted by the contingency of which it is the weightless, transparent envelope.”

What lies behind this void? We can never know until we move past and beyond it.

Structures, 20 Square, Silverlens Galleries, 05 June – 06 July 2013.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photograph. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.